Zinnias Will Attract Butterflies and Bees

Zinnias are excellent flowers for feeding the butterflies and bees that play such important roles in our ecosystems. Here are some fabulous zinnias to grow.

As an Amazon affiliate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

Zinnia flowers are dazzling sights in themselves, but they are simply colorful garden sculptures; their true beauty lies in the attraction of the lively and equally beautiful life forms that visit them. As the Monarch Butterfly Garden website states: "Zinnia flowers are a must-plant annual for the butterfly garden and a favorite flower of monarchs, swallowtails and those hyper-winged hummingbirds." Bees should, of course, be added to the list, for they can be as beautiful as any other visitors of note.

Zinnias and Butterflies

Although there are hundreds of zinnia selections in all shapes, sizes and colors, there is no single answer as to which zinnia is the best for attracting visitors. Most information is anecdotal and it simply reflects results from a single geographic area.

For example, according to interviews of gardeners conducted by the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, a gardener in Washington state considered the large-flowered garden zinnia (Zinnia elegans) called ‘Cut and Come Again’ as the best for large butterflies. Alternately, the Peruvian zinnia (Z. peruviana) was moderately attractive to small butterflies such as skippers—but a gardener in Minnesota claimed this zinnia didn’t attract butterflies at all. Instead, those butterflies preferred the large cactus-flowered and ‘Blue Point’ (also known as Benary’s Giant) zinnias and even the smaller flowered ‘Crystal White’ zinnias, while avoiding the so-called Mexican zinnia (Z. haageana) entirely. In Maryland the dwarf Star series was most attractive to butterflies, but members of another dwarf type, called the Profusion series, were not, yet those of the closely related Pinwheel series were.

As a consensus, The Monarch Butterfly Garden website lists the following zinnias as best for butterflies: ‘Zowie’, ‘State Fair’, ‘California Giant’, ‘Benary’s Giant’ and ‘Cut and Come Again’, yet it would seem that anecdotal evidence is of little specific guidance for attracting winged visitors. One sure way to know which zinnia works in your own garden is to plant different sorts and see what results.

There is scant experimental evidence for zinnia attractiveness, and it turns out to be more contradictory than expected. For example, a study done at the University of Kentucky contradicts the oft-cited notion that single flowers are more attractive to pollinators than double flowers. Using mixed-color stands of four zinnia varieties, it demonstrated that small, double-flowered zinnias such as ‘Lilliput’ were much more attractive than small single-flowered zinnias such as the Profusion series and even large double-flowered zinnias such as the Oklahoma series. As a result the researchers suggested that ‘Lilliput’ would be an “excellent choice for inclusion in butterfly gardens,” a suggestion rarely, if ever, mentioned among anecdotal evidence.

In South Carolina tests were conducted at Clemson University with another small, semi-double-flowered zinnia series called Peter Pan to determine if the arrangement of colors or the massing of colors was of importance for attracting butterflies. White, scarlet, pink and gold forms were mixed, with the conclusion that arranging colors randomly, in rows or in patches made no difference. White was the most visited by all the butterflies (14 species) except monarchs, which ignored them entirely, in favor of scarlet and to a lesser extent gold and pink.

In a complementary study, a total of 8 colors of Peter Pan were used to see what effect isolated patches of color would have, and what would be the most effective number of plants per patch. The study discovered that plots with 8 to 16 plants were more effective than those having up to 64 plants. In this case the greatest number of butterflies (15) was reported from two pink colors, followed by white, orange and plum, scarlet, gold and flame.

Regardless of how zinnias are arranged or their color, the above information can be taken only as a slight indication of preference among butterflies and, coupled with anecdotal suggestions, should act somewhat as a guide to their place in the garden.

Zinnias and Birds and Bees

Although honey bees and bumble bees are attracted to zinnia flowers, many kinds of solitary bees are as well. The disk flowers of zinnias are so small, relative to the overall size of the entire flower head, that tiny species of bees may be collecting nectar and pollen but they are easily overlooked.

Having worked with both bees and gardens in my adult life, I can assure most readers that no harm will come from bees in the garden. When bees work they take no interest in their surroundings. Some of the larger forms, such as bumble bees and carpenter bees, are so engrossed in their work you can even pet them (if you are as daft as an entomologist). Attempting to pick any bee up, however, is not recommended, as bees take offense at being handled.

As far back as 1869, Joseph Breck, the American seedsman and author, was mentioning birds as one of the delights of growing zinnias. He commented, “The little yellow-birds make sad havoc with this flower when seeding. They will pick the flowers all to pieces to get the seeds . . . and the ground under the plants is often covered with the fragments of the flower; but who can blame?”

Among birds attracted to zinnias are the humming sorts, which feed on nectar, and finches that feed on the dried seed heads—if for some odd reason the gardener has not removed them as recommended. Some gardeners may mistake the blurred visit of a hawk moth (also called sphinx moth) for a hummingbird, based on its incredibly fast wing beat and ability to hover. These moths have greatly elongated mouthparts, by which they obtain nectar without landing on a flower, just as in the case of hummingbirds.

Because little in the way of wildlife actually feeds on zinnia foliage or flowers—grasshoppers being a notable exception—nectar and pollen are their biggest attraction. And although pollinating visitors may, themselves, attract predators such as spiders and praying mantids, in general zinnias are free of pitched, food-induced battles, and so they serve as beautiful dinner plates for the birds and bees and butterflies.

Text by Eric Grissell, a gardener and entomologist, for the January/February 2017 issue of Horticulture.

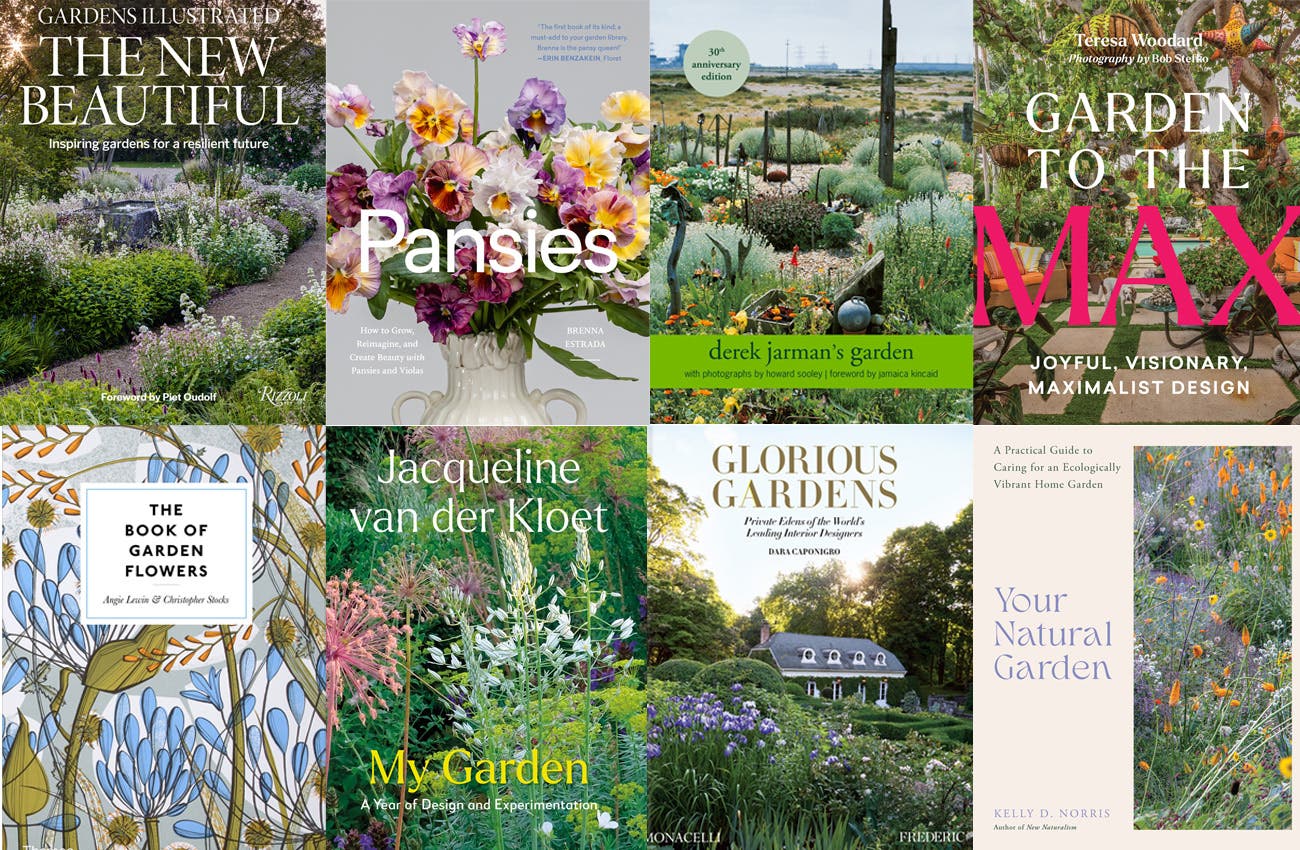

Recommended related reading:

Insects and Gardens by post author Eric Grissell

Nature’s Best Hope by Douglas Tallamy

Pollinator-Friendly Gardening by Rhonda Fleming Hayes