This article first appeared in Horticulture’s October 2014 issue. As an Amazon affiliate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

Raising plants from seeds is very satisfying, but it does have its challenges. The horticultural equivalent to cooking from scratch, it gives you a much fuller appreciation for your subject than simply “ordering out” plants from the garden center. There are also far, far more varieties available from seed catalogs than you can find for sale as potted seedlings. I have raised countless thousands of plants from seed over the years, with many failures and many successes. I never tire of watching tiny plants erupt from the soil, or of caring for them as they grow into beautiful adulthood. What follows are some simple tips that I hope will challenge you to raise your own plants from seed.

Remember that seeds are alive. Inside that hard shell a tiny plant races against time to germinate and grow before its food reserves are exhausted. Commercially available seed packets should be stamped with a harvest or “packed for” date so you know their contents are fresh. To retain viability, store your seed in a cool, dry place. At room temperature, many seeds deteriorate quickly, while they can last for years in the refrigerator. If you harvest your own seed, wait until the seed coat has turned tan, brown or black. Unripe seed, usually white or green, will not survive drying and storage. I like to spread my harvested seed onto sheets of paper and let it dry indoors for a few weeks before I clean and package it. Try to separate the seed from capsules, pods and debris. A kitchen strainer is handy for separating small seeds and a rolling pin works well to lightly crush capsules.

Just add water. Most vegetables and annual flowers sprout quickly after sowing if kept moist and warm. I start annuals such as Mexican sunflower (Tithonia rotundifolia ‘Goldfinger’) and unusual tomatoes such as the deep purple ‘Indigo Rose’ in a small greenhouse in early spring, though a sunny window or bank of grow lights works equally well. Sow them in a potting mix formulated for seeds, water them well and keep them at room temperature. Once you water the seeds, they awaken from their dormancy and begin to swell and grow. If you let the pots dry out after this point, the seeds can easily die. This is one of the most common reasons seed fails to germinate.

Understand species versus hybrids. The embryo within a seed inherited traits from both its mother and father. In the wild, the parents are usually from the same species and fairly similar, so seed collected from the mother plant will grow to be nearly identical to it. However, we humans appreciate novelty and seek unusual variations in flower color, height, leaf shape and taste to enliven our gardens and cuisine. Just like your children may or may not inherit your emerald eyes, seed from unusual varieties may or may not be like either parent. If you sow seed from, say, a white-flowered coneflower (Echinacea ‘White Swan’), likely some seedlings will be white and the rest purple. Your chances of getting all white coneflowers or all purple tomatoes increase if you have no other variety nearby. You can further up your averages if you hand-pollinate the plants with a paintbrush or feather.

It is often possible to combine two closely or even distantly related species and obtain viable hybrid seed. Many garden flowers and some vegetables are of hybrid origin. Hybrids possess a greater jumble of genes than species, and hence a greater variation in form, flower and fruit. Sometimes when we grow related species together in a garden, spontaneous hybrids appear too. Coreopsis בMoonbeam’ is just such a spontaneous hybrid. This popular perennial blooms heavily through the year, because, like many hybrids, it is sterile, never producing seed. Thus all its energy can go to blooming. So remember, seed from hybrids is likely to produce plants with different characteristics, or you may not find any viable seed to collect.

Seeds tell time. Unlike annual species, most hardy perennial, tree and shrub seed will not germinate immediately after sowing, for these temperate plants have to factor winter into their plans. Coneflowers, coreopsis and a host of other species require a chilling period after sowing to overcome dormancy. It is important to understand that dry, cold storage is not sufficient. The seed needs to absorb water first for the cold treatment to work. The length of chilling depends on the plant, but 90 days is a good average; it works for 95 percent of species I have tried. You can mix the seed with damp moss or potting soil in a self-sealing plastic bag and place it in the refrigerator for three months, or simply sow the seed in fall and leave it outdoors to go through a natural winter.

Some seed is impermeable. Lupines, roses, morning glories, many cacti and New Jersey tea are among a smaller set of plants whose seeds need pretreatment to germinate well. These have an outer layer that prevents the seed from absorbing water, necessary for germination, from the soil. The seed sits there for months, or even years, until the coating has weathered away. Luckily, it is easy to speed this process by rubbing the seed between two pieces of sandpaper for about 30 seconds prior to planting. To check that I have scarified the seed properly, I soak it in water for 24 hours to see that it swells.

Tiny seeds need light. Once a seed germinates, it must push up through the soil and fight its way through the competition for its place in the sun. Larger seeds and the seedlings they contain have the resources to push through fairly easily, but seeds smaller than a grain of sand will often not germinate unless they are exposed to light after sowing. Blue lobelia (Lobelia syphilitica) is one example. In the wild it grows along streams and pond shores where water scours soil and exposes the seeds; in the garden, some vigorous raking around the plants accomplishes the same. Whether you sow small seeds in pots or into garden soil, do not cover them, and water them carefully though frequently until they pop up.

Some seeds are recalcitrant. Though 90 percent of seeds will respond to some combination of the treatments above, there is a small group—mostly woodland wildflowers from North America and Eurasia—that are far more challenging. Trilliums, Solomon’s seals, peonies, bloodroot, hepaticas and hellebores are all what seed ecologists call recalcitrant. They are intolerant of dry storage and even when handled fresh they may take several winters and summers to germinate. The easiest method by far is to plant the seeds directly in the garden or in specially designated raised seed beds and wait. If you are lucky, you may even get a few self-sown seedlings popping up under the mother plant, too.

Be they trilliums or tomatoes, I hope you try growing some plants from seed. Bringing plants from infancy to adulthood fosters a connection and understanding of their needs and wants that you just cannot get by simply buying the potted plants from the nursery. It is a fun and inexpensive way to add great variety to your gardens, too.

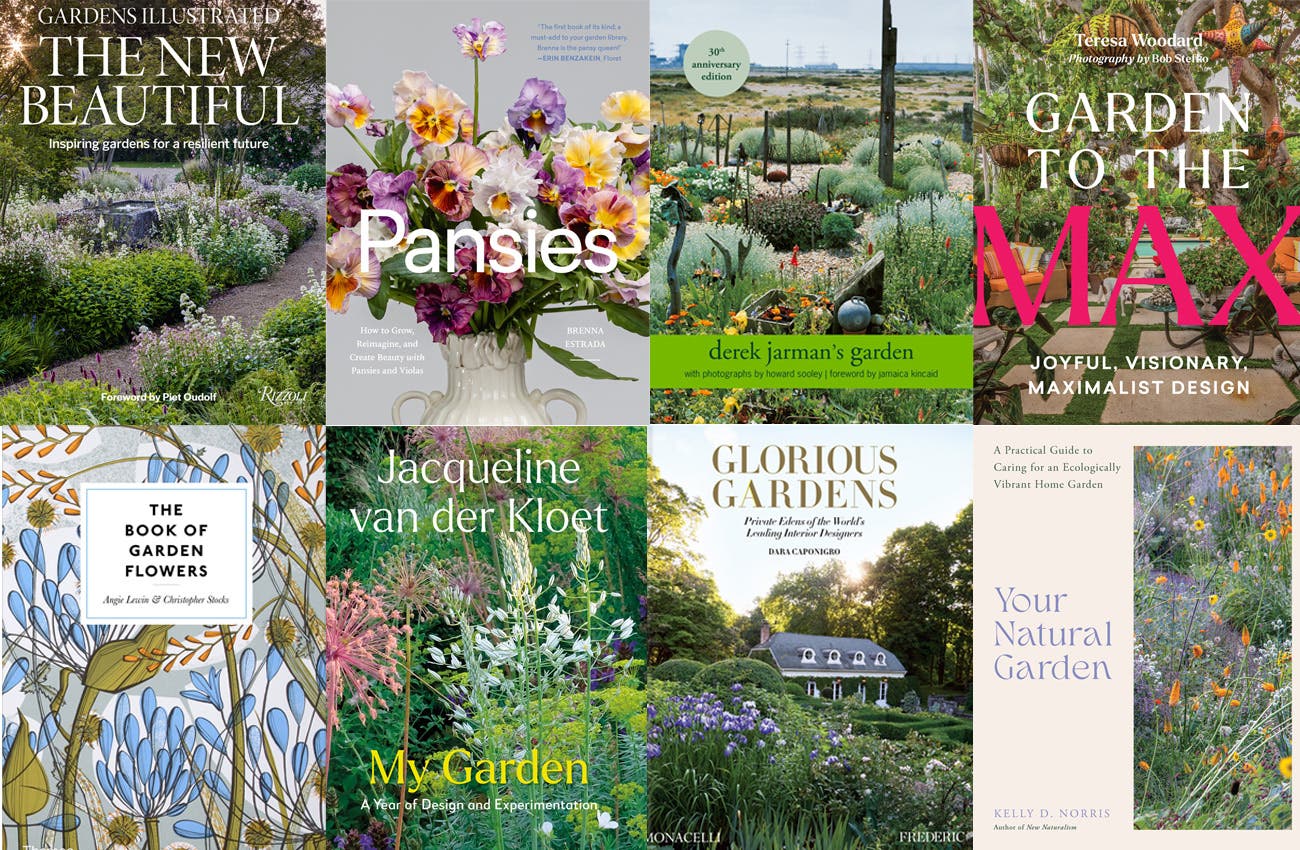

Editor's Recommended Reading:

Bill Cullina shares unparalleled advice and inspiration for gardening with North American native plants in his classic Growing and Propagating Wildflowers of the United States and Canada.

Ken Druse covers seed preparation, sowing and more, plus other propagation techniques such as taking softwood cuttings, in his thorough, science-based yet highly readable Making More Plants.

In Starting & Saving Seeds, Julie Thompson-Adolf focuses on propagating edible and ornamental garden plants from seed, and she covers how to harvest, clean, dry and store seeds for the next season.