Knowing what to look for will help you get the most out of any garden tour

by GORDON HAY WARD illustrations by GILL TOMBLIN

Visiting a garden—whether public or private—is a rare treat. We gardeners are usually so busy in our own plots that we rarely take the time for such a luxury. When we do make the effort, we return to our garden with a fresh eye with which to reevaluate it.

What we get out of visiting a garden, however, is not up to the garden—it's up to us. Too often we walk into a visit with our critical faculties primed. We look to see what we like, but we are equally prepared to see what we don't like. Of course, we need to have standards against which to measure gardens we visit. We certainly won't grow as gardeners if we don't. On the other hand, if we explore a new garden on its own terms, a whole world of new design and plant ideas will open up.

My wife, Mary, and I have been leading garden tours to England for the past ten years, and leading visitors through our own garden and those of clients for nearly twice as long. What we hear time and again is one question: “What is that plant?” While it is certainly a valid question, there is so much more to be gained by garden visiting. Let the following questions be a guide to you on your next visit to a garden.

THE HOUSE

Many houses are set within a garden, while others might be at the very edge of it-or not even visible from the garden at all. If the house is right at the outset of your tour, or if you have been invited to walk through the house to get to the garden, pay attention.

- When approaching the house, is it clear which is the appropriate door to enter? What signals did the designer provide to lead you there?

- From inside the house, do other doors lead to important paths? Do certain windows focus attention on specific views?

- What do you notice about the relationship of materials used on the exterior of the house to those materials used in the garden? Do you see the repetition of brick, stone, or wooden surfaces in both?

- Notice the proportion of beds or paved sitting areas near the house, relative to the proportions of the house itself.

THE PROPERTY

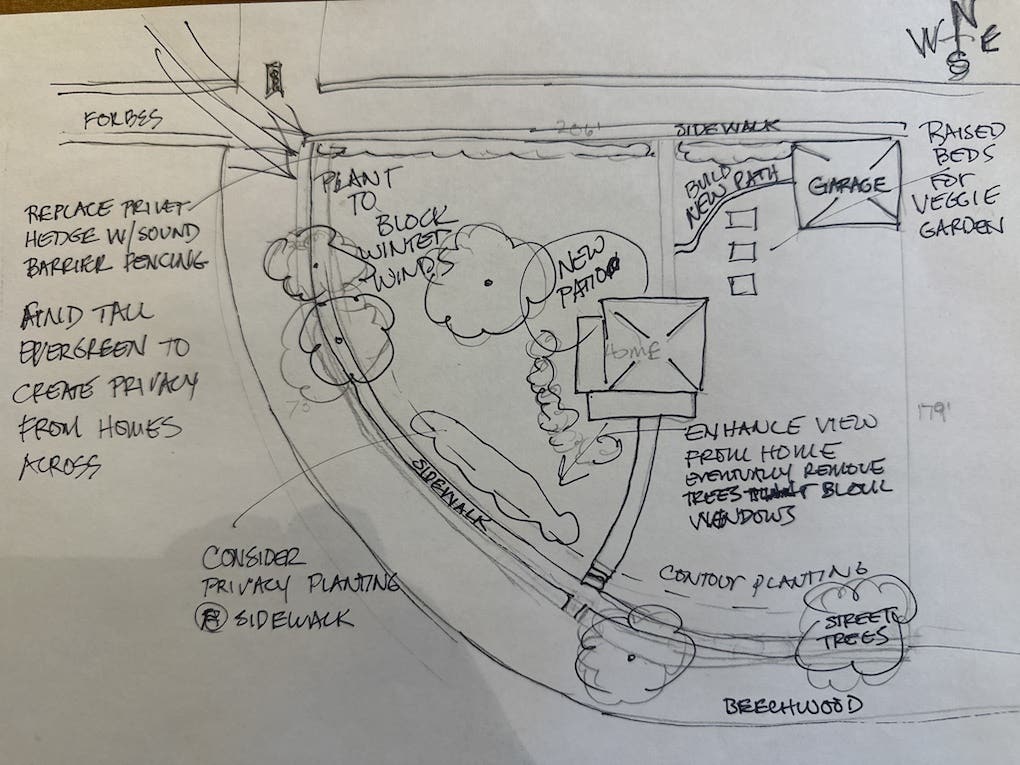

Once you know'a bit about the relationship between house and garden, you need to get a sense of the layout of the entire property. The owners of many public and some private gardens offer maps. First, find north and orient yourself to the four points of the compass. This knowledge will help you understand plant choice and a vast range of other decisions as they relate to patterns of sun and shade. Then take a moment to orient yourself in relation to the garden areas you can see from the entrance.

- Do individual garden areas have names?

- What USDA zone is the garden in?

- Are all parts linked together by paths flowing from one enclosed area to the next, or do separate garden areas appear as isolated islands in a sea of lawn?

- Is the whole garden open, with one area virtually indistinguishable from the next?

If it is not possible to get a map, and it seems appropriate, take a quick walk through the entire garden. Note as you go how its parts fit (or don't fit) together.

THE GARDEN CONSERVANCY'S OPEN DAYS

Put these questions to the test throughout the year with the Garden Conservancy's Open Days. Each year, the Garden Conservancy gives you an entree into North America's finest private gardens. Their 2002 edition of The Garden Conservancy's Open Days Directory contains information on more than 400 gardens, from Oregon to Maine.

Highlights for this year include a certified butterfly habitat in Dallas, complete with a waterfall and koi pond; “El Chaparro,” a California native garden in urban Los Angeles that brings the botanical wilds into the city; and at least a dozen new gardens thoughout Illinois. The cost for visiting each garden is $5.

To order the 2002 edition, call 888-842-2442. It costs $1 5.95 ($10.95 for members of the Conservancy) plus $4.50 shipping and handling. It includes both driving directions to each garden and descriptions provided by the hosts. For more on the Garden Conservancy, visit their web site at www.gardenconservancy.org.

THE SUM OF ITS PARTS

Once you've seen the whole garden, go back to the beginning and take a deeper, more measured look, following your initial path.

- Do different garden areas have different functions? For example, are some for sitting while others are for strolling through? Are some for outdoor entertainment and others for appreciating color and texture contrasts?

- How do light and shade change from area to area?

- Notice when straight and curved bed edges are used. Do curved bed edges move around a tree, boulder, or large shrub?

- What fragrances are you aware of?

- How do lawn shapes relate to bed shapes? Are the two in proportion?

- Do some areas feel too big, to the point where they demand too much attention? Do some areas feel confining?

Also, pay attention to how water is used in the garden. It can excite or calm emotions; it can produce sound or remain silent.

TRANSITIONS

A good garden design takes advantage of transition areas. Gates, doorways, arbors, pergolas, a pair of standing stones, or a break in a wall or hedge can all mark transitions. Designers also signal transitions by placing plants or ornaments on stepping stones, gravel, brick, stone, or other materials. Pay attention to how transition zones are handled, for you may want to build them into your own garden.

- Are there marked transitions, or do areas blend imperceptibly?

- Are there steps or ramps at the point of transition, and if so, what materials did the designer use?

- Do straight paths visually link one area to another by allowing a view, or are sight lines down long paths closed by doors or hedges?

The top of a set of stairs is an important transition point because it directs the view. The grander the steps, the grander the view you should see from the top step.

THE LANDSCAPE

As you walk through, ask yourself questions about the relationship of the garden proper to the natural world beyond.

- Is the garden enclosed and separate from that natural world, or do views and paths link the garden to the larger landscape?

- Are there plants, benches, paths, or other garden elements that draw you from the garden into the surrounding woods, meadows, prairie, or fields?

Once you have visited several gardens and you want to use your experience, make a list of problems you're trying to solve in your garden: how to make transitions from one area to the next, how to use a specific perennial or shrub in a border, how to site outdoor structures or garden ornaments. Then think about how each designer solved the same problems you're wrestling with. Through the process of comparison, you'll begin to see how designers work.

STRUCTURES & ARCHITECTURE

Pergolas, gazebos, and arbors act as magnets that draw you along a specific route. They also provide intimate spaces from which to take in vistas. Upright supports, doorways, or windows also frame views of the garden and beyond. Structures should be built in a style that is appropriate for the space. We have a rustic grape arbor, for example, adjacent to a 100-year-old garden shed. On the other hand, at the end of a 90-foot-long, 8-foot-wide, straight lawn path between two mixed borders, we built a refined gazebo. The furniture under the arbor is simple, while the chairs and bench we chose for the gazebo are considerably more refined.

- What architectural elements exist in the garden?

- How does the structure's material support the mood of the garden?

- What vines, if any, grow on the structure?

THE PLANTS

Once you have an understanding of the design and layout of a garden, you can then begin to zero in on the crux of the matter-plants! Look at both individual plants as well as how they combine with others into a distinctive whole. How does plant choice support or establish the mood of the area? For example, our outdoor dining area is in the shade, and the plants around it should be subordinate to the conversation at the table. Thus, we planted hostas, ferns, and subtle groundcovers to create a subdued mood. On the other hand, for a view down the length of a pair of mixed borders, we chose exciting, dramatic, bold plants for full sun.

- When looking at a bed, what are the structure plants—the dominant trees, shrubs, or large perennials—that are repeated within a garden area?

- What plants fill in the spaces between those structure plants?

- Did the designer focus on a certain bloom period or color scheme?

- Do certain colors, foliage shapes, or types of plants dominate?

- How are trees used in the garden? As individual specimens? As repeated structural elements? As architectural forms or as natural elements? Is there a wide variety of trees in the garden, or do certain ones dominate?

- What is the level of maintenance and the feeling that it creates in each area? Does the whole garden stand erect or is there an ease about the way it is kept up? Or is the garden so poorly maintained that deadheading has not been done, weeds abound, and edges are sloppy? Before reaching a personal judgment about the level of maintenance, try to understand the designer's purpose and style.

- And finally…what's that plant?

GARDEN-VISIT ETIQUETTE

- DON'T: TAKE CUTTINGS, SEED HEADS, FRUITS, OR BERRIES

- WANDER FROM PATHS INTO PLANTED BEDS

- TALK TO OTHERS IN YOUR GROUP WHEN A GUIDE OR OWNER IS SPEAKING

- SHOW UP BEFORE OPENING TIME AND ASK TO BE ADMITTED

- STAY BEYOND CLOSING TIME

- ASK TO USE THE FACILITIES IN THE HOUSE

- TAKE FOOD INTO THE GARDEN WITHOUT PERMISSION

- DROP REFUSE, PAPERS, OR THE LIKE

- TAKE PHOTOGRAPHS OR SET UP A CAMERA TRIPOD WITHOUT ASKING PERMISSION